After hip replacements, a lawsuit: Implant company paid Penn surgeon consulting fees

By Josh Goldstein, Inquirer staff writer

Katrina McKenzie and husband, Woodrow. Hip implants she received at Penn failed.

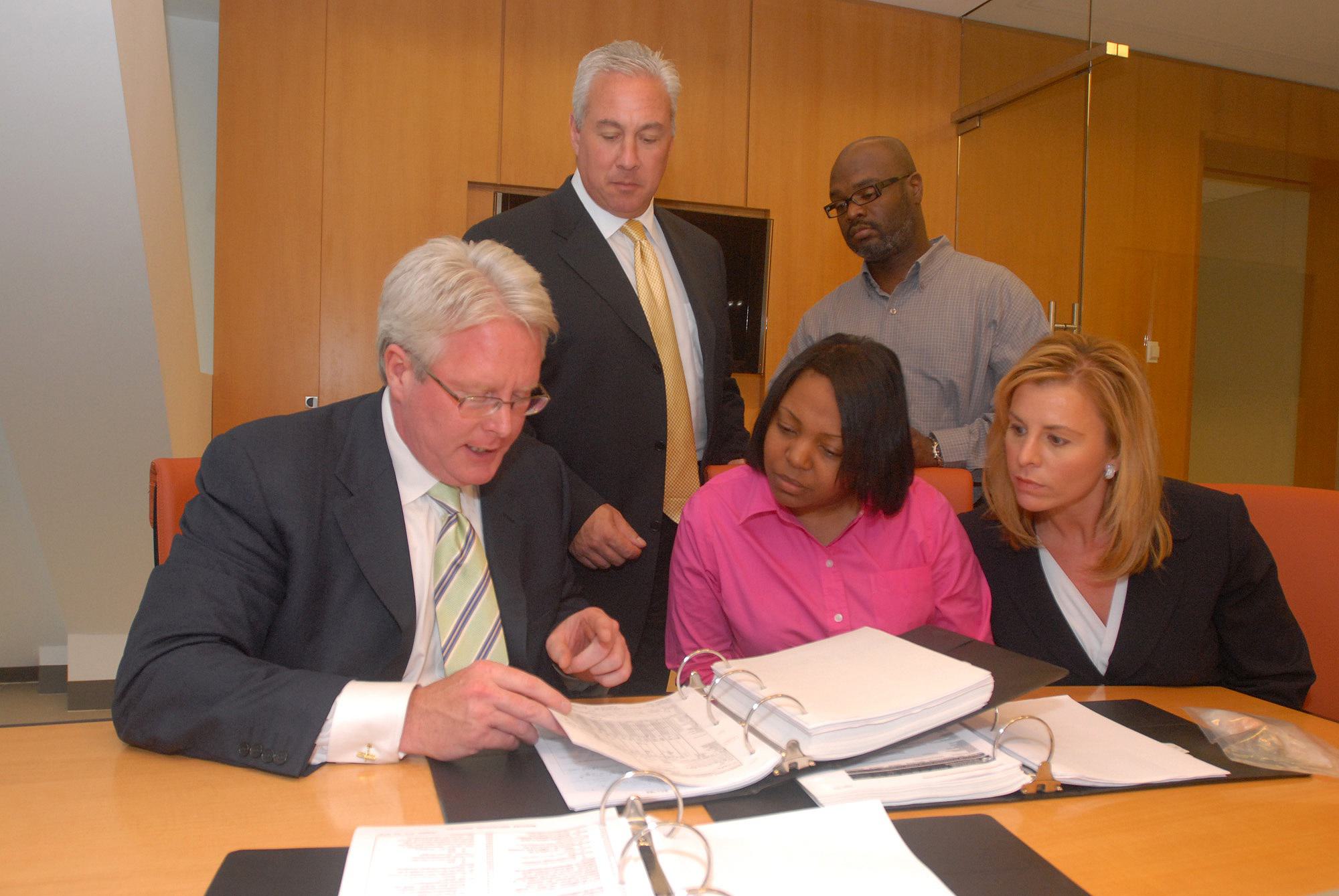

Implant patient and lawsuit plaintiff Katrina McKenzie goes over medical files with attorney Tom Duffy (left). Standing (right rear) is McKenzie’s husband Woodrow.

Fed up with the constant pain in her hips, Katrina McKenzie took her surgeon's advice and had them replaced with experimental implants.

The 31-year-old from Galloway, N.J., who agreed to participate in a clinical study, knew there was a risk that her new hips could fail.

But she didn't know that the manufacturer financing the study, Smith & Nephew, was also paying her surgeon tens of thousands of dollars a year as a consultant.

In recent years, such payments to doctors from medical implant manufacturers and drug companies have become increasingly controversial.

Some leading orthopedic surgeons receive six- and seven-figure payments annually, in the form of royalties, consulting deals and speaking fees from the makers of artificial hips and knees.

These arrangements - and the eye-opening amounts - have prompted federal investigations and debate in Congress, which is considering legislation to force companies to disclose the payments.

McKenzie filed suit against the University of Pennsylvania Health System and her surgeon, Jonathan Garino, contending that he botched her surgery and that the consulting fees affected his decisions.

Garino and Penn responded, in court filings, that McKenzie received good care and that the payments had no effect on her treatment.

"On the merits of the medicine, we are going to vigorously defend this case," said Susan E. Phillips, spokeswoman for the Penn health system.

After the birth of her first child, the hip pain that began during McKenzie's pregnancy grew worse. In July 2002, she went to see Garino.

Her X-rays showed that bone in both hips had collapsed, according to court records. Garino recommended replacing both joints with a new type of implant made by Smith & Nephew.

At the time, the artificial hip was used in Europe, but not here. Garino was part of a clinical study aimed at winning approval for the new implant from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “It eventually was approved,” he said.

In a deposition, Garino testified that he expected the ceramic-on-ceramic implants he recommended for McKenzie would "last longer than metal on plastic by a significant time frame."

That was particularly important for someone like McKenzie, who was about half the age of a typical hip-implant patient.

He also said that if McKenzie had voiced any reservations about participating in the study, he would have used an FDA-approved model.

On Aug. 20, 2002, Garino replaced both of McKenzie's hips during a four-hour operation at Pennsylvania Hospital.

In his deposition, Garino said that while Smith & Nephew sponsored the study, he did not receive any direct financial benefit. The company paid Penn for the surgeon's time and expenses.

However, under questioning from one of McKenzie's lawyers, Garino acknowledged that he was being paid for other work by Smith & Nephew - which he did not disclose.

At the time of McKenzie's surgery, Garino estimated, he was making "$20,000 to $50,000 annually" as a Smith & Nephew consultant.

He was paid $200 to $400 an hour to do "things like instruct other surgeons how to use devices, how to do their surgery better, give lectures at Smith & Nephew-sponsored courses, provide ideas for improvement of products. . . . Things of that nature."

Asked during a deposition if he had told McKenzie or other patients that he was paid by the company, Garino said "I did not."

Garino's failure to disclose that work was contrary to Penn policy, which says that doctors must tell patients about any financial relationship with the company sponsoring a clinical trial, said Penn's Phillips.

Asked whether Garino was disciplined, Phillips said, "We don't comment on personnel matters."

At follow-up exams, McKenzie claims, she complained to Garino of persistent pain, instability and trouble walking. The hip squeaked when she moved, McKenzie said.

Garino reassured her that the implants were in "satisfactory position without evidence of loosening or wear," she said in the lawsuit.

Ultimately, McKenzie went to other doctors who told her the implants had worn out. She underwent two additional operations to have them redone.

McKenzie's lawyers argue the surgeon hid her post-op problems to support the company's bid for FDA approval.

"I think it is a definite conflict of interest," said her attorney, Tom Duffy. "Doctors, only being human, are going to start to make decisions about who should have surgery and what devices to use based on their pocketbooks."

Lawyers for Garino and Penn denied any negligence in McKenzie's surgery and follow-up care. In court filings, they said Garino did not misrepresent the results of the surgery to McKenzie or to anyone else.

Penn's Phillips said, "Any relationship that Dr. Garino has or had with Smith & Nephew did not impact the care the patient received."

The lawsuit is scheduled for trial in August.

Like more than two dozen other local surgeons, Garino continues to receive substantial payments from device makers. In 2007, Garino got $75,000 from Smith & Nephew and $250,000 from another manufacturer, Depuy Orthopaedics, according to company disclosures.

In response to written questions from The Inquirer, Garino said that "the vast majority of payments to me are royalties for joint replacements that I developed."