Feature Article on Tom Duffy: “Even When He’s Flying, He’s Grounded...”

This article was originally published in the October 2018 issue of "The Verdict," the monthly newsletter of the Philadelphia Trial Lawyers Association.

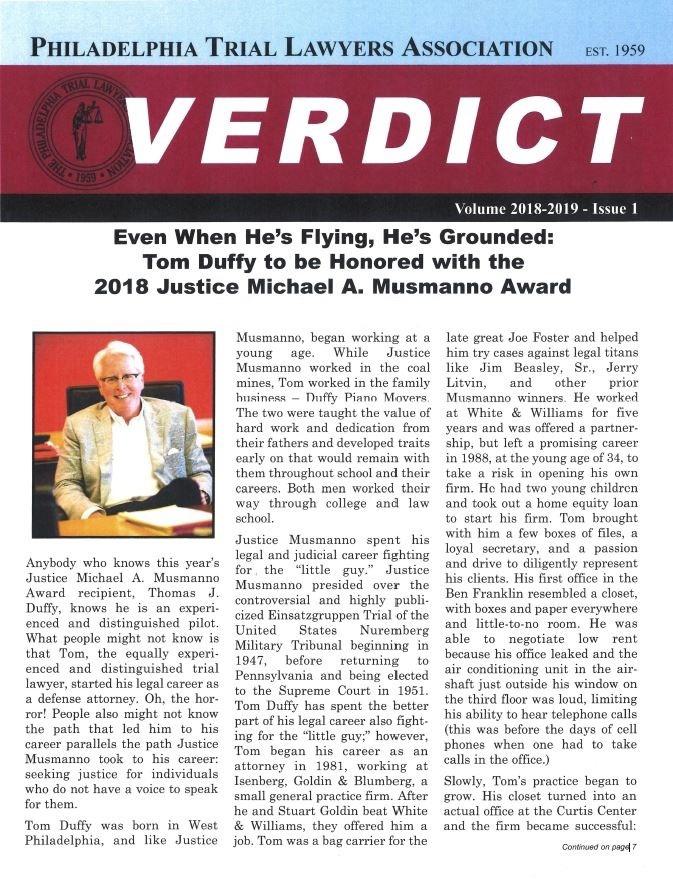

Anybody who knows this year's Justice Michael A. Musmanno Award recipient, Thomas J. Duffy, knows he is an experienced and distinguished pilot. What people might not know is that Tom, the equally experienced and distinguished trial lawyer, started his legal career as a defense attorney. Oh, the horror! People also might not know the path that led him to his career parallels the path Justice Musmanno took to his career: seeking justice for individuals who do not have a voice to speak for them.

Tom Duffy was born in West Philadelphia, and like Justice Musmanno, began working at a young age. While Justice Musmanno worked in the coal mines, Tom worked in the family business - Duffy Piano Movers. The two were taught the value of hard work and dedication from their fathers and developed traits early on that would remain with them throughout school and their careers. Both men worked their way through college and law school.

Justice Musmanno spent his legal and judicial career fighting for the "little guy." Justice Musmanno presided over the controversial and highly publicized Einsatzgruppen Trial of the United States Nuremberg Military Tribunal beginning in 1947, before returning to Pennsylvania and being elected to the Supreme Court in 1951. Tom Duffy has spent the better part of his legal career also fighting for the "little guy;" however, Tom began his career as an attorney in 1981, working at Isenberg, Goldin & Blumberg, a small general practice firm. After he and Stuart Goldin beat White & Williams, they offered him a job. Tom was a bag carrier for the late great Joe Foster and helped him try cases against legal titans like Jim Beasley, Sr., Jerry Litvin, and other prior Musmanno winners. He worked at White & Williams for five years and was offered a partnership, but left a promising career in 1988, at the young age of 34, to take a risk in opening his own firm. He had two young children and took out a home equity loan to start his firm. Tom brought with him a few boxes of files, a loyal secretary, and a passion and drive to diligently represent his clients. His first office in the Ben Franklin resembled a closet, with boxes and paper everywhere and little-to-no room. He was able to negotiate low rent because his office leaked and the air conditioning unit in the airshaft just outside his window on the third floor was loud, limiting his ability to hear telephone calls (this was before the days of cell phones when one had to take calls in the office.)

Slowly, Tom's practice began to grow. His closet turned into an actual office at the Curtis Center and the firm became successful: it had clients and a steady flow of work coming in. Things were going well: now he had three children at home and a buzzing defense practice. But then, a revelation occurred.

Tom was tasked with defending a school bus driver who crushed a student's ankle, requiring surgery. Tom negotiated with plaintiffs counsel, but his offer was rejected and the matter proceeded to trial. At trial, the jury found for the defendant bus driver. Tom's client began sobbing at counsel table, crying

out that she did run over the little boy's foot and did this mean he was not going to get any money. Tom looked at her and looked at the little boy and realized this was not the kind of career he wanted. He wanted to fight for clients like the little boy, who had been innocently hurt by the negligence of others and needed someone to speak up for them. Tom returned to his office and spoke with the attorneys and staff. He explained his desire to "switch sides," so to speak, which was met with puzzled looks and questions of "how?"

At the time Tom made his decision, the firm, Duffy & Quinn, had many insurance company clients, new files coming in every day, and a steady stream of income to burn the lights and pay salaries. But it was wrong. So, following the bus driver trial, Tom picked up the phone one day and made call after call to his insurance company clients and terminated his relationship with them. Each call was similar: "Tom are you nuts, we are sending you all our work, what are you doing?!" Tom responded to each question that what he was doing was "the right thing." There was one particular client who would not "let" Tom terminate the relationship, which resulted in the uncontracted fee being tripled that day. The relationship ended minutes thereafter. Tom's partner at the time, Jeff Quinn, would continue to handle defense cases and they amicably separated with Tom handing Jeff over 500 cases so he could successfully continue his defense practice. From that day forward, Tom only represented plaintiffs. As Justice Musmanno once said, "[o]ne of [the] inescapable obligations [of a hospital] is that it must exercise a proper degree of care for its patients, and, to the extent that it fails in that care, it should be liable in damages."1 Tom has continued to make sure that any defendant who fails in its inescapable obligation to act reasonably is held accountable.

Tom has always made it a point to treat each client like family. They were not numbers, checks, or results; they were friends, cousins, sisters, and uncles. Tom would open his home on Thanksgiving for clients who had no place to go; he visited clients who were bedridden at home, brought them magazines, and kept them company; he visited people in the hospital and held their hands during procedures. He knelt and prayed with them, he attended their funerals, he cried with them. Tom has sat with clients when life support has been withdrawn from their family members. Of course, it was not all "heavy." Tom has attended the weddings of clients, been the godfather of their children, and has sang with them at mass. He has been honored to have clients' children named after him and has changed the lives of hundreds of families.

After years of helping people in and out of the courtroom, Tom realized he still wanted to do more and perhaps he could help by empowering organizations that also helped people. So, in 2012, he established the "Duffy Fellowship," through which he fully underwrites an attorney's salary at some of Philadelphia's foremost legal service nonprofit organizations. Currently, "Duffy Fellows" serve at the Legal Clinic for the Disabled, Community Legal Services, and at the Homeless Advocacy Project. By creating and funding this tremendous Fellowship, Tom has helped some of Philadelphia's poorest residents tackle problems such as unsafe housing and living conditions, children's health issues, income insecurity, and obtaining public benefits. Tom continues to be committed to making a difference in peoples' lives, every way he possibly can.

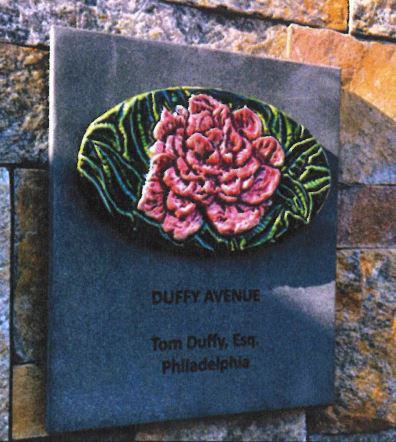

Tom also serves as a member of the Board of Trustees of the Magee Rehabilitation Hospital Foundation. In 2016, the "Creative Therapy Center and Healing Gardens" broke ground on the roof of Magee Hospital, and Tom was honored with a portion of the space being named "Duffy Avenue." Tom has made countless donations to the hospital over the years. In fact, only Anna Magee, the namesake of the hospital, has donated more personal money to the hospital than Tom.

Tom has helped not only clients, but also lawyers, and has been on the Board of "Lawyers Concerned for Lawyers," for 25 years, helping attorneys with alcohol and drug addictions and other issues re-establish their legal careers so they can continue to help others as well. Tom has also been active in the Philadelphia Trial Lawyers Association, and served in various roles before becoming President in 2012. He continues to be committed to PTLA and is always advocating for small firms and solo practitioners, as well as the next generation of trial lawyers, to become more involved.

Tom's legal work on behalf of his clients has made great law for all personal injury plaintiffs, including the recent and oft-cited case of Deeds v. Univ. of Pa. Med. Ctr. 2 In Deeds, the Pennsylvania Superior Court overturned a defense verdict, holding that Tom's clients were entitled to a new trial because of defense counsel's repeated references to governmental benefits (the Affordable Care Act), a patent violation of the well-established collateral source rule. Additionally, in Straub v. Cherne Indus., 3 the Pennsylvania Supreme Court held that a defendant's failure to object to an inconsistent verdict constituted a waiver of the issue, reversing the Superior Court's grant of defendant's judgment non obstante veredicto and reinstating a multi-million-dollar verdict for Tom's clients. Both cases are often cited as favorable decisions for accident victims.

Through it all, Tom has never forgotten where he came from. He was one of seven kids raised in a small row home in West Philadelphia. His father was a piano mover and his mother a homemaker. He worked his way through college, and started working full-time before going to Temple Law School at night. Tom appreciates his good fortune and is determined to help those less fortunate. He can always be seen with a smile on his face, and he is truly happiest when he is helping others.

All members of the bench and bar are invited to attend the Justice Michael A. Musmanno Award Dinner, Wednesday, October 24, 2018, at The Bellevue in Philadelphia. Cocktails begin at 5:30 p.m., dinner to follow. Please contact the PTLA Office for more information.

1. Flagiello v. Pennsylvania Hospital, 208 A.2d 193 (Pa. 1965).

2. Deeds v. Univ. of Pa. Med. Ctr., 110 A.3d 1009 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2015).

3. Straub v. Cherne Indus., 880 A.2d 561 (Pa. 2005).